Come Live with Me, the movie that most closely models your life, holds perhaps a final key for interpreting your life, or at least a final note to end on. You play a Viennese refugee, Johnnie, who will be deported to Europe unless she can find a husband in one week. You strike a deal with a down-and-out writer, George, played by Jimmy Stewart: if he will marry you on paper, you will provide him with a weekly allowance so he can continue to write and eventually pay her back. Ironically, this deal inspires him to write a story about their arrangement—Without Love—which he is able to sell for a handsome sum. Of course, he ends up falling in love with you and the usual complications follow.

Two decades after the film, Stewart described an encounter with an “old guy” who remembered a “’picture show’ in which the actor said a poem about fireflies” (TMC). He couldn’t remember the film, but his fondness for it moved Stewart.

The actor commented: “That’s the thing, that’s the great thing about movies. If you’re good and God helps you and you’re lucky enough to have a personality that comes across, you’re giving people little, little pieces of time—pieces of time that they never forget.”

The scene that so impressed the “old guy” occurs late in the movie was at the farm house of the writer’s grandmother.

Not yet united, they are lodged in separate rooms divided by a three-wall under exposed rafters.

Earlier, the writer has supplied her with a toothbrush and flashlight. Looking out her window and trying to delay his leave-taking, he notices fireflies and begins to explain to her their mating ritual.

Bill: Lots of fireflies tonight….We certainly do have a lot of fireflies around here.

Johnnie: Yes, fireflies are very nice.

Bill: I’m glad you like them….You know very much about fireflies? As a matter of fact, it’s pretty interesting. You know, all those little lights really mean something. They use them to signal each other…and the way they signal each other….ah…gee….hmh?

Johnnie: I didn’t say anything.

Bill: Eh, no. You didn’t. Well, the man firefly he always knows pretty much where he stands.

Eh…may…be…uh…maybe I can explain it to you a little better like this. When the girl firefly wants to let the man firefly know that she sort of likes him a little bit she flashes that little light at exact two-second intervals. Eh…eh… that’s on the level. It’s been timed. Don’t you think that’s pretty smart?

Johnnie: Oh, yes. I do. I do. Good night.

Bill: I always thought that was pretty smart…for fireflies.

[It’s a lot smarter when it’s expressed by a human!]

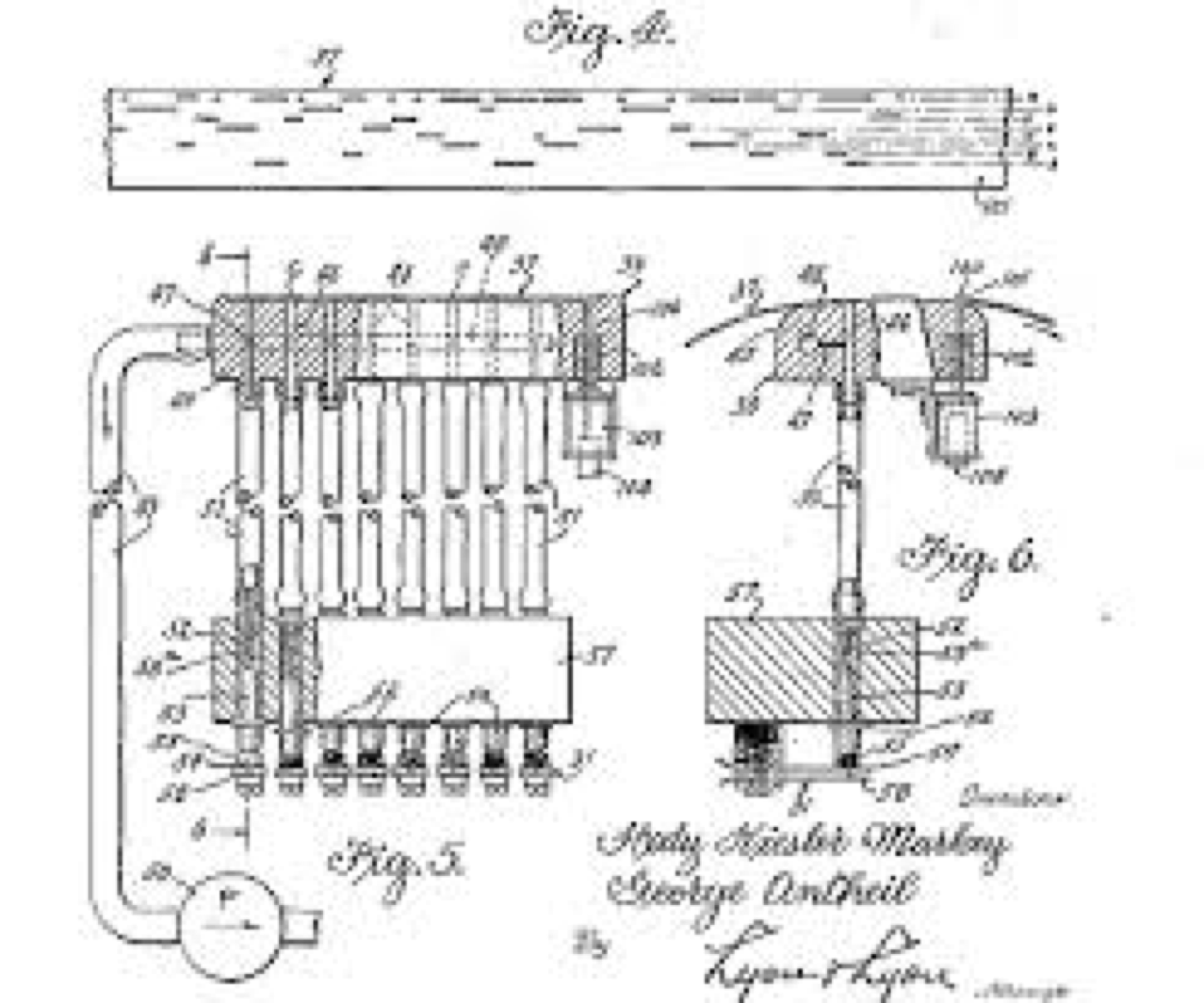

“The mechanism arranged as described, functions to light the lamp for a short time during each transition from one to another of the useful channels D, E, F, and G, to warn the operator not to transmit a control impulse at the moment of transition from one frequency to another. The lamp remains lighted throughout periods when the transmitter is tuned to transmit in any one of the channels A, B, or C, to mislead the enemy, but he will know, by the fact that the lamp is lighted, that these impulses will not affect the torpedo.”

Later, in his adjoining room, Bill recites for her Marlowe’s “Come Live with Me” with a halting delivery, hesitating between the rhythms and the words he tries to recall. Touched, lying in bed, she accepts his romantic gesture, the darkness now punctuated by the flickering of the flashlight illuminating her face with its dreamy, cameo qualities.

Simply put, a small piece of time.

But the dreamy Hollywood image is not the note we should end on.

Surely the idea of frequency flashing fireflies was of your own invention—and once again unattributed to you while you had to listen to it being played back to you in a lecture by Stewart.

The signals that best express your life are not the evenly spaced ones described here; rather, they are ones that have been disrupted and interrupted. They can only be recovered by recreating and filtering out the noise that obscures them.

Until then, the hands on the keys remain ghostly, not your own.